How whole-body activities are linked to reading success.

I learned a long time ago; recess was as important as reading, writing and ‘rithmetic. I vividly recall the exhilaration of the children as they bolted out the door to freedom. As soon as they were released, children zipped by in groups and singularly; arms, legs, and voices a blur of sudden activity. Informally, sections of the playground were designated for a specific activity. The climbers would already be at the top of the jungle gym while hopscotchers began to chalk the grid and pick their stones. A competition between future NBA stars would be underway where the hoops stood while a haphazard game of chase between the boys and the girls immediately commenced. A couple of children would hug the wall, already reading a book or just observing the chaos. Eagle eyed teachers would remind those children it was time to play and watch to break up any bullying.

The last group would dance around the teacher to hold one end of a long jump rope while a line would form to take turns jumping in. As a rookie, I wanted my alone time on the playground to yuck it up with the other teachers, but I was in for a major lesson myself.

It took a seasoned 1st grade teacher to set me straight about why every child needed to master jump roping to become a successful reader.

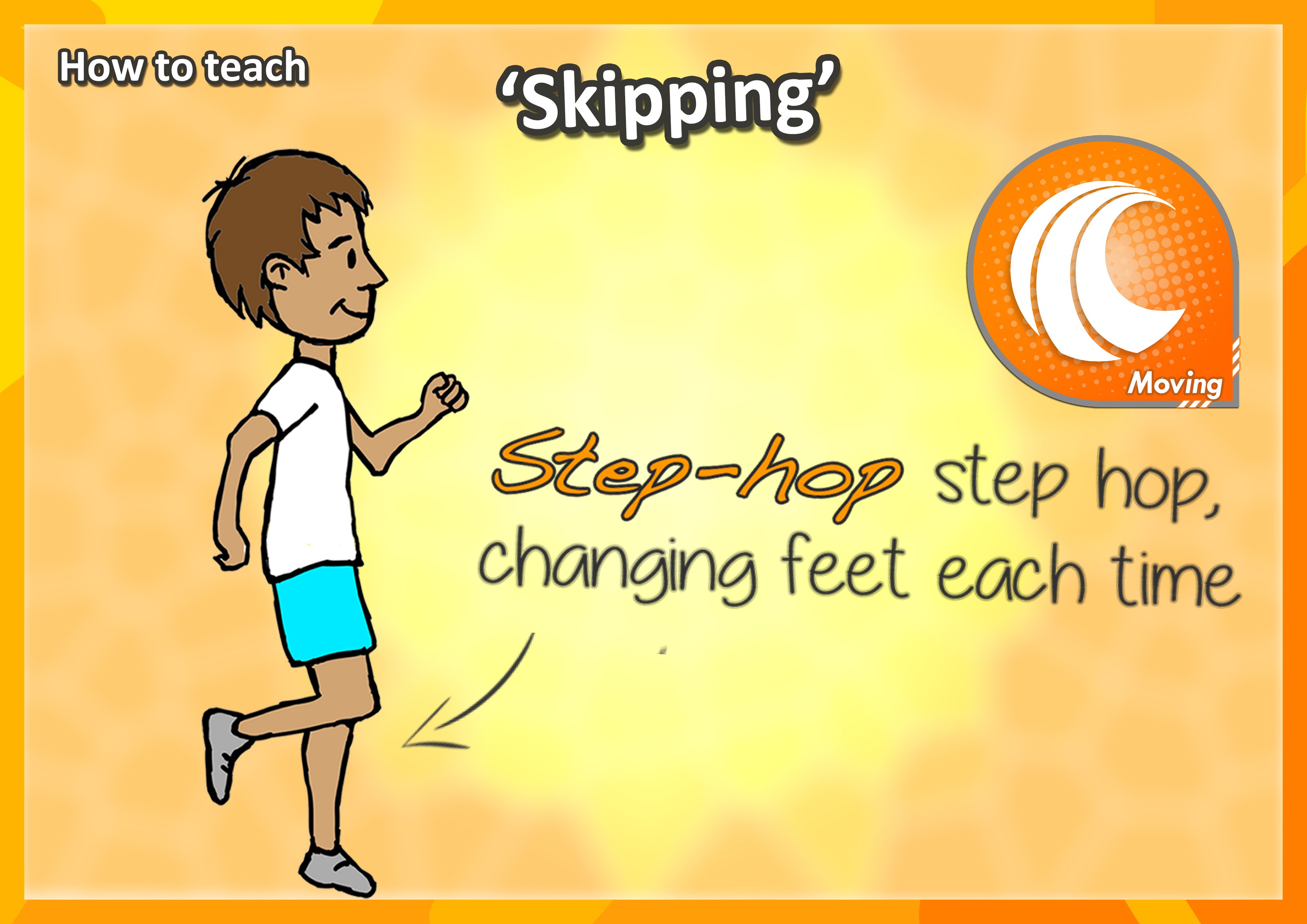

To many, recess is nothing more than an opportunity for children to let off some steam. Classroom teachers do not disagree as they watch their most antsy students let loose after sitting for long periods of time. A little drizzle never stopped a teacher from bundling everyone up for recess when the four walls of the room begin to close in on everyone. When recess is tacked onto lunch, children are known to take two bites and try to get outside as soon as possible. The value of physical movement during the day has been validated by countless studies. However, my mentor made it clear running the playground is fine, but if you wanted to improve a child’s reading proficiency, get the jump rope out. Children who practice “jumping in” are actually working the part of the brain that links letters/sounds together into words. Equally important, skipping in a game of chase and navigating a hopscotch grid develops cross-lateral skills at the same time.

If you have never considered the academic benefits of physical activities before, there is plenty of proof that physical movement enhances reading in a whole new way. “Neuro scientists and researchers, actually, have known this for some time. But the message has not yet made it to everyone who works with children. Reading requires the same cooperation between the two brain hemispheres. To start reading a line of text on the left, the right brain is in control. At the midline, it must hand off to the left brain to continue reading to the end of the line.”

A few years ago, an observant PE teacher noticed a pocket of 1st graders unable to skip proficiently. The teacher noted most of the non-skippers also struggled to read. Together, the PE teacher and classroom teacher instituted daily opportunities for the class to engage in physical activities with a focus on skipping. By the end of the year, not only could these children skip up a storm, but their reading levels improved as well. What is interesting to note, as children have become less and less active in their school day, they have become less active at home as well.

But the back-to-basics movement pushes back against wasting time letting children step away from directed instruction in the classroom. Critics say recess is unnecessary and if children need to move, there is plenty of time during PE. To make a case for adding interactive, physical activities to the curriculum requires the administration and staff to embrace the whole child as a learner. Off the playground and without a single word in sight, several other whole-body activities are linked to reading success. Clapping chants, puzzling and energetic dancing involving crossing the midline offer opportunities to uses the brain creatively and practices the area in the brain where reading occurs. Quite honestly, it is reading without words. Systematically approached, teachers who add these types of whole-body activities to their curriculum have discovered measurable improvement in the reading proficiency of their students. Movement is not just for children in the lower grades, either. And the new flexible seating arrangements of the classroom is a step in the right direction. Every age group from preschool through high school would benefit from training the brain through movement.

When parents ask me how to help their children become better readers, the first thing I say is back away from books for a while. As parents stare at me in disbelief, I ask them to hear me out. I ask if their child can skip, to which, most parents are uncertain. I ask if there are any jump ropes in the house or if the child can ride a two-wheel bike. Often parents pipe in quickly “my child has a scooter, but he doesn’t really like his bike.” Of course, their child prefers the scooter because riding a bike requires a multitude of developmental skills which must be practiced to master. It’s then that I explain the whole brain-body connection to reading.

When parents ask me how to help their children become better readers, the first thing I say is back away from books for a while. As parents stare at me in disbelief, I ask them to hear me out. I ask if their child can skip, to which, most parents are uncertain. I ask if there are any jump ropes in the house or if the child can ride a two-wheel bike. Often parents pipe in quickly “my child has a scooter, but he doesn’t really like his bike.” Of course, their child prefers the scooter because riding a bike requires a multitude of developmental skills which must be practiced to master. It’s then that I explain the whole brain-body connection to reading.

My mentor shared a final piece of wisdom which I have shared with my peers, administrators and parents throughout my career. Children who have lost their first tooth, can tie their shoes, mastered skipping, jumping in, riding a two-wheel bike and able to complete a 100-piece puzzle usually have the developmental skills to “break code” and begin to truly read. If you want to help your child become a better reader, put the majority of the books on the shelf for a while. Involve your child in a variety of whole body physical activities.

Have a few puzzles readily available to be completed again, and again. Eventually bring books back slowly, starting in a comfy environment with the parent as the reader and the child as the audience. Embrace the fluency of the words, the beauty of the pictures and message of the story, together. Leave the instruction to the classroom teacher unless otherwise informed.

Recess was never the same after I understood how it impacted classroom performance. I made it my mission to make sure every one of my kindergartners took a couple of turns jumping in at jump rope before going off on their own. Years later, I was fortunate to run a preschool program within a gymnastics center where thirty minutes of movement in a full gymnastic center anchored our three-hour day. I am certain the inclusion of daily gross motor activities eliminated many behavioral issues for the classroom teachers and enhanced academic instruction. In fact, if a child had an extraordinary amount of energy to burn, that child would participate in two sessions of movement daily. Physical activities benefit more than just the youngest of children, however.

My husband, a fourth-grade teacher, was known as the “King of Kickball.” As children were lining up for recess in his class, the jockeying began for places, positions, and teams for the daily recess game of kickball.  As he got older, the greatest honor in his class would be being chosen as Mr. B’s runner to take the bases in place of the king. In hindsight, there was a lot more going on than just a lively game of kickball. Today, nearly ten years after his retirement, I still meet young adults who ask if Mr. B remembers playing kickball at recess. Teachers of long ago knew the value of the type of physical activities necessary to academic success which are practiced on the playground at recess. Somewhere along the way, the value got lost in the strive to push academics through drill and repetition at a desk in the classroom. Whether recess is all of ten minutes long or a heavenly twenty minutes, its impact in the classroom can be both immediate and long lasting. After all, it is practicing reading without any words at all!

As he got older, the greatest honor in his class would be being chosen as Mr. B’s runner to take the bases in place of the king. In hindsight, there was a lot more going on than just a lively game of kickball. Today, nearly ten years after his retirement, I still meet young adults who ask if Mr. B remembers playing kickball at recess. Teachers of long ago knew the value of the type of physical activities necessary to academic success which are practiced on the playground at recess. Somewhere along the way, the value got lost in the strive to push academics through drill and repetition at a desk in the classroom. Whether recess is all of ten minutes long or a heavenly twenty minutes, its impact in the classroom can be both immediate and long lasting. After all, it is practicing reading without any words at all!

Leave a Reply